Recently on twitter I asked for advice on computational modelling and/or computational neuroscience courses, in particular summer schools for early career researchers. I received quite a few suggestions so thought I would create a list for anyone else who is interested. Note, I only know about these courses through recommendations and/or the information on their website. For some, the link is for a previous years course, so I can't guarantee they are definitely still running. Still, I hope the list proves useful for some.

Computational modelling of cognition with applications to society

http://escop.eu/news/conferences-news/third-european-summer-school-on-computational-modeling-of-cognition-with-applications-to-society-/

Advanced course in computational neuroscience

http://www.accn.pt/venue/lisbon-portugal/previous-course-editions

Computational psychiatry course (Zurich)

http://translationalneuromodeling.org/cpcourse/

Computational psychiatry course (London)

https://sites.google.com/site/comppsychcourse/2015schedule

Summer school in computational sensory-motor neuroscience (CoSMo)

http://www.compneurosci.com/CoSMo/

Model-based neuroscience summer school

http://www.modelbasedneuroscience.com/

OIST computational neuroscience course

https://groups.oist.jp/ocnc

Brains, minds and machines

http://www.mbl.edu/education/special-topics-courses/brains-minds-and-machines/

Computational neuroscience and the hybrid brain

http://www.nncn.de/en/news/events/computational-neuroscience-hybrid-brain

ACT-R spring school and master class

http://act-r.psy.cmu.edu/?post_type=announcement&p=15589

If anyone else has further suggestions, I'm happy to continue to update this list. Just leave a comment with the link and name of the course.

Thursday, 22 October 2015

Thursday, 2 July 2015

Research briefing: Evidence for holistic episodic recollection via hippocampal pattern completion

Horner, A.J., Bisby, J., Bush, D., Lin, W-J., & Burgess, N. (2015) Evidence for holisitic episodic recollection via hippocampal pattern completion, Nature Communications, 6:7462 doi: 10.1038/ncomms8462

Think back to your last birthday.

Perhaps you were at home, eating good food. Perhaps you were in a pub, drinking

good beer. Perhaps you were in a club, dancing to terrible music.

When we recall events like these

from our past we are able to re-immerse ourselves in the experience, as if we

were there once again. You might remember being in your dining room, eating

birthday cake, whilst your friends sing happy birthday. You might even remember

incidental details, like what you were thinking at the time or the music

playing in the background. How do we remember and re-experience these complex

events?

A long-standing theory,

originally proposed by Marr but developed by many others, suggests that the individual

elements of a complex event are represented in distinct neocortical regions.

For example, the faces of our friends might be represented in visual regions in

the ventral temporal lobe whilst the background music might be represented in

auditory regions in the lateral temporal lobe. These distinct elements are

thought to be bound in a single coherent memory – what Tulving referred to as

an ‘event engram’. It is the hippocampus, receiving input from multiple

neocortical regions (acting as a ‘convergence zone’ in the words of Damasio),

that is thought to form these event engrams when we first experience an event.

What happens when remembering

this event at a later date? Perhaps you meet a friend who attended your

birthday party. This friend acts as a ‘cue’ to retrieve the previous event. Importantly,

with a single cue we are able to retrieve the entire event. In this case, we

see our friend and that enables us to remember the room we were in, our

birthday cake, the background music etc. This retrieval of a complete memory

from a partial cue is known as ‘pattern completion’ and is thought to be a key

function of the hippocampus (and particularly subfield CA3 of the hippocampus).

Following this pattern completion process in the hippocampus, all the retrieved

elements are thought to be ‘reinstated’ in the neocortex. In other words, the

same representations that were active when we first experienced an event become

active at retrieval. It is this hippocampal pattern completion process,

followed by reinstatement of all event elements in the neocortex, that is

thought to underpin ‘recollection’ – our ability to subjectively re-experience

a previous life event.

Despite a wealth of evidence for

the involvement of the human hippocampus in episodic memory, and recollection

in particular, evidence has not been presented for this pattern completion

process in relation to the retrieval of complex events.

Participants learnt pairwise

associations of locations (e.g., kitchen), famous people (e.g., Barack Obama),

objects (e.g., hammer) or animals (e.g., dog). Importantly, each pairwise

association overlapped with other associations, forming complex ‘associative

structures’ (see Figure 1). For example, you might learn ‘Kitchen-Obama’ on one

trial, ‘Obama-hammer’ on a second trial and ‘hammer-kitchen’ on a third trial.

As such, we build relationships between multiple elements across separate

encoding trials. This is an example of a ‘closed-loop’ structure, where each

element is paired with each other element (forming a triangle of associations).

This closed-loop condition is compared to ‘open-loop’ structures, where a chain

of three associations is formed between four elements (see Figure 1).

Importantly, both conditions are formed from three pairwise associations across

three encoding trials. Participants are asked to vividly imagine the two

elements for each association ‘interacting in a meaningful way’.

At retrieval we tested each

pairwise association. For example, we cued with ‘Obama’ and participants were

required to retrieve ‘kitchen’. They were shown six elements of the same type

(locations in this example) and asked to select the element (kitchen)

originally paired with the cue (Obama). The retrieval trials were identical for

both the closed-loop and open-loop condition.

How does this allow us to look

for pattern completion? If pattern completion is present then when retrieving a

single element, all other elements should also be retrieved. In our example,

when cued with ‘Obama’ and retrieving ‘kitchen’ the object associated with

these two elements (‘hammer’) should also be retrieved. This is despite

‘hammer’ being task-irrelevant during this trial.

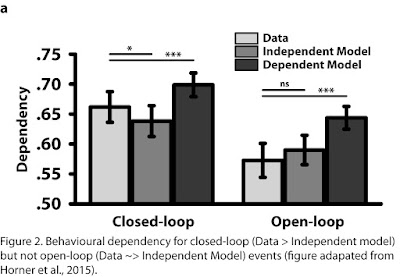

This retrieval should have behavioural

consequences – retrieval accuracy for any two elements within an event should

be related (called ‘behavioural dependency’). If you successfully retrieve

‘kitchen’ when cued with ‘Obama’, you should be more likely to retrieve

‘hammer’ when cued with ‘Obama’. This is because your retrieval success for one

element is based on the strengths of all the associations for a single event. We

provide evidence for this ‘behavioural dependency’ in our closed-loop, but not

open-loop, condition (see Figure 2). This suggests, despite their similarity at

both encoding and retrieval, that pattern completion is present in the

closed-loop but not the open-loop condition.

This retrieval should have behavioural

consequences – retrieval accuracy for any two elements within an event should

be related (called ‘behavioural dependency’). If you successfully retrieve

‘kitchen’ when cued with ‘Obama’, you should be more likely to retrieve

‘hammer’ when cued with ‘Obama’. This is because your retrieval success for one

element is based on the strengths of all the associations for a single event. We

provide evidence for this ‘behavioural dependency’ in our closed-loop, but not

open-loop, condition (see Figure 2). This suggests, despite their similarity at

both encoding and retrieval, that pattern completion is present in the

closed-loop but not the open-loop condition.  If pattern completion is present

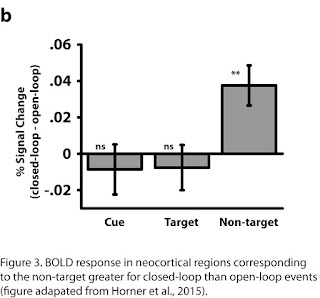

in the closed-loop condition we should see reinstatement of all elements in the

neocortex – including the ‘non-target’ element. Using fMRI, we identified

neocortical regions associated with the encoding/retrieval of individual

elements. Locations were associated with the parahippocampal gyrus, famous

people with the medial prefrontal cortex and objects/animals with lateral

occipital cortex. We next looked for ‘reinstatement’ of non-target elements. If

cuing with a location, and retrieving a person, we should also see

reinstatement in the region associated with objects/animals. We found greater

activity in non-target regions for closed-loops relative to open-loops, again

consistent with pattern completion in the closed-loop but not open-loop

condition (see Figure 3). Importantly, we also show this ‘behavioural

dependency’ and retrieval of non-target element in a computational model of the

hippocampus (an attractor network model), further demonstrating the presence of

pattern completion in the closed-loop but not the open-loop condition.

If pattern completion is present

in the closed-loop condition we should see reinstatement of all elements in the

neocortex – including the ‘non-target’ element. Using fMRI, we identified

neocortical regions associated with the encoding/retrieval of individual

elements. Locations were associated with the parahippocampal gyrus, famous

people with the medial prefrontal cortex and objects/animals with lateral

occipital cortex. We next looked for ‘reinstatement’ of non-target elements. If

cuing with a location, and retrieving a person, we should also see

reinstatement in the region associated with objects/animals. We found greater

activity in non-target regions for closed-loops relative to open-loops, again

consistent with pattern completion in the closed-loop but not open-loop

condition (see Figure 3). Importantly, we also show this ‘behavioural

dependency’ and retrieval of non-target element in a computational model of the

hippocampus (an attractor network model), further demonstrating the presence of

pattern completion in the closed-loop but not the open-loop condition.

Finally, we correlated this

‘non-target’ reinstatement with the BOLD response across the whole brain to see

what other regions correlated with reinstatement. This revealed the hippocampus

(see Figure 4). The BOLD response in the hippocampus correlated (across

participants) with the amount of neocortical reinstatement for the non-target

element. This result supports the idea that the hippocampus is performing

pattern completion, retrieving all event elements, allowing for the

reinstatement of these elements in the neocortex.

What is critical to our study is

that we always compare the closed-loop relative to the open-loop condition. In

both conditions participants have learnt a series of overlapping pairwise

associations and are successfully performing pairwise associative retrieval. As

such, all our results are related to processes over-and-above simple pairwise

associative retrieval. It is this careful experimental design that we believe

is critical to our ability to infer the presence of pattern completion in our

data.

To summarise, we have presented behavioural,

computational modelling and fMRI evidence for hippocampal pattern completion

and neocortical reinstatement in humans, and related these processes to the

retrieval of complex events. We believe this is the first evidence to support a

long-standing mechanistic account of recollection – our ability to subjectively

re-experience previous life events.

Monday, 18 May 2015

The academic parent #5 – the aftermath

It has now been about five weeks

since I finished full time paternity leave, looking after my daughter when my

wife went back to work after nine months. We are now both back at work, and my

daughter is going to nursery three days a week. I’m off today to look after

her, and she is currently blissfully asleep.

Looking back on my paternity

leave, it seems ridiculous that I ever considered not doing it. I took a month

of holiday, so it wasn't a long period of time in the grand scheme of things.

When I returned to work nothing seemed to have changed. Other people’s projects

had moved on slightly, but not to the extent that I now feel I'm

underperforming in any significant way. It is clear I won’t be as productive

this academic year as I might ordinarily have been, but I just had a child – so

yeah.

Apart from actually looking after

your baby and spending time with them, the best thing about taking leave is the

shared experience. Suddenly all those joys, annoyances, trials and tribulations

that my wife would tell me about became real. She would get home from work and

we would have the same conversation as we always had, just in reverse. I can’t

express how good this is for a relationship rapidly adjusting to a new way of

living.

Despite this, the experience isn't

the same. My daughter now sleeps through the night, naps regularly during the

day, and is predominantly a smiling happy child. Looking after her was hard,

but I didn't experience the sheer fear of looking after a helpless newborn

alone, whilst suffering chronic sleep deprivation. Equally, although my wife

has now shared in the adjustments required when going back to work (see: the academic parent #1), she hasn't experienced dealing with work

when chronically sleep deprived. I remember having scientific conversations

whilst getting coffee where I had to accept that I just couldn't contribute. My

mind wasn't working well enough to have any meaningful discussion. Equally, the

guilt of leaving for work knowing full well how bloody hard it's going to be

for my wife was hard. I think when my wife went back to work it was more

bemusement than anything else. She knew I'd be fine, but wanted to see how I'd

initially get basic stuff wrong (I did).

The last day of paternity leave

was a mix of emotions. My daughter decided to have one of her rare stroppy

days. She was crying and whining for most of the day. That meant I spent much

of the day counting down the hours until her bedtime. When it finally arrived I put

her in her cot and closed her bedroom door. I sighed with relief, and then wished I could have spent a bit more time with her.

Wednesday, 18 March 2015

Some thoughts on the UCL “Is Science Broken” debate

[Disclaimer: This was written the day after the event, and I took no notes. If I have misrepresented the opinions of any of the panel members then it is a result of my poor attention during, and poor memory following, the debate. My apologies to those involved if this is the case.]

For those that weren't aware, UCL hosted a talk and debate last night entitled “Is Science Broken? If so, how can we fix it?” Chris Chambers (@chriscd77) gave a talk about the recent introduction of Registered Reports in the journal Cortex. This was followed by a broader panel discussion on the problems facing science (and psychology in particular) and how initiatives, such as pre-registration, might be able to improve things. Alongside Chris, Dorothy Bishop (@deevybee), Sam Schwarzkopf (@sampendu), Neuroskeptic (@Neuro_Skeptic) and Sophie Scott (@sophiescott) took part in the debate, and David Shanks chaired.

For those that weren't aware, UCL hosted a talk and debate last night entitled “Is Science Broken? If so, how can we fix it?” Chris Chambers (@chriscd77) gave a talk about the recent introduction of Registered Reports in the journal Cortex. This was followed by a broader panel discussion on the problems facing science (and psychology in particular) and how initiatives, such as pre-registration, might be able to improve things. Alongside Chris, Dorothy Bishop (@deevybee), Sam Schwarzkopf (@sampendu), Neuroskeptic (@Neuro_Skeptic) and Sophie Scott (@sophiescott) took part in the debate, and David Shanks chaired.

First, I found

Chris’ talk very informative and measured. Words such as “evangelist” are often

bandied about on social media. Personally, I found him to be passionate about

pre-registration but very realistic and honest about how pre-registration fits

into the broader movement of “improving science”. He spend at least half of his

talk answering questions that he has received following similar presentations

over the last few months. I would guess about 90% of these questions were

essentially logistical – “will I be able to submit elsewhere once I've

collected the results?”, “couldn't a reviewer scoop my idea and publish whilst

I’m data collecting?” It is obviously incumbent upon Chris, given he has

introduced a new journal format, to answer these legitimate logistical

questions clearly. I think he did a great job in this regard. I can’t help feeling

some of these questions come from individuals who are actually ideologically

opposed to the idea, trying to bring about death by a thousand cuts. Often

these questions implicitly compare pre-registration to an “ideal” scenario,

rather than to the current status quo. As a result, I feel Chris has to point

out that their concern applies equally to the current publishing model. I may

just be misreading, but if people are ideologically opposed to pre-registration

I’d rather they just come out and say it instead of raising a million and one

small logistical concerns.

On to the

debate. This worked really well. It is rare to get five well-informed

individuals on the same stage talking openly about science. There was a lot of

common ground. First, everyone agreed there should be more sharing of data

between labs (though the specifics of this weren't discussed in detail, so

there may have been disagreement on how to go about doing this). Dorothy also

raised legitimate ethical concerns about how to anonymise patient data to allow

for data sharing. There was also common ground in relation to replication,

though Chris and Neuroskeptic both cautioned against only replicating

within-lab, and pushed for more between-lab replication efforts, relative to

Sophie.

Where I think

there was disagreement was in relation to the structures that we put in place

to encourage good practice (or discourage bad practice). On several occasions

Chris asked how we were going to ensure scientists do what they should be doing

(replicating, data sharing, not p-hacking etc.). Essentially it boils down to

how much scope we give individual scientists to do what they want to do.

Pre-registration binds scientists (once the initial review process has been

accepted) to perform an experiment in a very specific way and to perform specific

statistics on the data collected. This should (though we need data, as pointed

out by both Chris and Sam) decrease the prevalence of certain issues, such as

p-hacking or the file drawer problem. You can’t get away from the fact that it

is a way of controlling scientists though. I think some people find that

uncomfortable, and to a certain extent I can understand why. However, what is key to pre-registration is that

it is the scientists themselves who are binding their own hands. It is masochistic

rather than sadistic. Chris isn't telling any individual scientist how to run

their experiment, he is simply asking scientists to clearly state what they are

going to do before they do it. Given the huge multivariate datasets we collect

in cognitive neuroscience, giving individuals a little less wiggle room is

probably a good thing.

Sophie pointed

out at the beginning of the debate that science isn't measured in individual

papers. In one hundred years no-one will remember what we did, let alone that

specific paper we published in Nature or Neuron (or Cortex). This is a reasonable

point, but I couldn't quite see how it undermined the introduction of formats

such as pre-registration. I don’t think anyone would claim a pre-registered

paper is “truth”. The success (or failure) of pre-registration will be measured

across hundreds of papers. The “unit” of science doesn't change as a result of

pre-registration.

Where I found

common ground with Sophie was in her emphasis on individual people rather than

structures (e.g., specific journal formats). Certainly, we need to get the

correct structures in place to ensure we are producing reliable replicable

results. However, whilst discussing these structural changes we should never

lose sight of the fact that science progresses because of the amazingly

talented, enthusiastic, nerdy, focussed, well-intentioned, honest, funny, weird,

clever people who design the experiments, collect the data, run the statistics

and write the papers. The debate wonderfully underlined this point. We had

five individuals (and a great audience) all arguing passionately about science. It is that raw

enthusiasm that gives me hope about the future of science more than any change

in journal format.

Monday, 16 March 2015

The academic parent #4 - things wot I learned

A brief list of things I have learnt in the space of less than a week:

- Looking after your child on a daily basis is tiring. One day, it's a doddle. However, several consecutive days on your own and it starts to get to you. Both my wife and I have been shattered this last week. She has been adjusting to life back at work and I have been adjusting to the life of a full time carer. Hopefully we'll have a bit more energy this week and not have to go to bed at 9pm every night.

- You're constantly thinking several hours ahead. When should I feed next, is it time for a nap, if I go for a walk now will she fall asleep and therefore not nap at home? Get your timings right and everything works wonderfully. Get them wrong and you end up spending 6 hours straight with a grumpy baby and no backup to help you out.

- Trips to the shops are now the best thing ever. You get out the house and your child gets some fresh air and visual stimulation. Even if it's just walking down the road to buy some milk it can break up an afternoon into two more manageable chunks of time.

- Don't sit down and have a cup of tea at the start of a nap. Before I knew it about an hour had gone by and I had been staring at the ceiling. I try to get straight on the computer so I can at least catch up on a few emails (whilst drinking my tea). That way I feel I haven't completely wasted my free time.

- It's great. Try it.

Wednesday, 11 March 2015

The academic parent #3 – the return of paternity leave

Today I am back on paternity

leave. My daughter is nine months old and my wife has returned to work. Rather

than send our daughter straight to nursery, we thought it might be a good idea

if I look after her full time for a month. We have done this for several reasons,

which I will explain below. I had toyed with the idea of taking time off for a while (in addition to the paternity leave I took immediately

after she was born), but it was a chance meeting at a conference dinner that

really got me thinking. I was chatting to a lecturer who had returned to work

following maternity leave, and she was explaining how her husband was taking 3

months of paternity leave. I explained I would like to do something similar,

but given I’m currently a postdoc who is thinking about future jobs and perhaps

needs a few more publications under his belt it wasn't the best timing for me.

This was obviously crap, and luckily she called me out on it. There is never a “convenient”

time to take paternity/maternity leave. There will always be an excuse. Since

then the plan has been relatively set in stone, at least in my mind.

So, why take leave now? First, because

I want to. I want to experience at least a small part of what my wife has been

through the past nine months. It won’t be the same, it will be easier for me,

but it will be close enough. More importantly, I want to spend more time with

my daughter when she is still a baby. Second, because I can. I have an

understanding boss and work in a supportive department. I may not be in this

situation again so I should take these opportunities when they present

themselves. Third, because it makes financial sense. Rather than take official

paternity leave, I’m essentially taking all my annual leave in one go. I don’t

think I have ever used up my allotted annual leave in a year. Most academics

probably don’t. For this year at least that is what I am doing. This means,

after a few months of statutory pay, my wife and I will both be on full pay for

a month without nursery costs. This will help a lot. It would not have been

financially viable for me to take official paternity leave, and therefore not be

paid during this time, as we would not have had enough income between the two

of us to cope. Fourth, because going back to work after nine months of

maternity leave is a big deal, and having to cope with the emotion of leaving

your child at the nursery seems like quite a lot to handle all at once. This

way my wife can be at work knowing I’m looking after our daughter, at least for

a few weeks.

Finally, because more men need to

take time off work and look after their kids. I've had very mixed reactions to

taking (only) one month off. Some have sounded shocked, others have asked what

I’m going to do with my time (answer: look after my daughter). It’s that mix of

reactions that made me realise it was the right thing to do on top of all the

personal reasons listed above. If it’s still a shock that a man might take time

off work to look after their child (and I reiterate, it is only one month so it

really isn't that significant) then we live in a pretty weird society.

Tuesday, 10 March 2015

The academic parent #2 – work-life balance

A recent article in Nature nicely highlighted some of the difficulties associated with juggling both work

and parenting responsibilities whilst trying to maintain some semblance of a

social life. Needless to say, it isn’t easy. Whilst I found the article to be

an honest and frank assessment of the trials and tribulations of parenthood and

academia, I couldn’t help feeling that part of the discussion was missing.

We are introduced to several

research active scientists who plan weeks ahead, call on

friends/colleagues/parents to help with child care, work into the evening once

their child has gone to bed, all in the quest to maintain their pre-child

levels of work. For instance, during maternity/paternity leave one couple

“planned to use [their child’s] nap times and evenings at home to work on data

analysis, manuscripts and grant proposals”. Another example tells of how the

“couple typically works side-by-side in their home office for three to four

hours” after they have put their daughter to bed.

It’s great that these individuals

are managing to find time to be a parent and be productive at the same time –

although their social life seems to have suffered somewhat. However, my issue

with the whole article is it presents two options (1) maintain previous work

patterns and be a bad parent or (2) change work patterns but maintain the same

working hours and be a good parent. At no point is the concept of working fewer

hours brought in for consideration. I’m not saying this is the correct

solution, but surely it is a viable option? Everyone agrees that academics can

work long hours, reviewing papers in the evening, spending all night finishing

a grant application, collecting data on the weekend. Given this common

agreement, why is it not remotely conceivable that one might want to cut down

on these hours once one has a child?

My issue with a lot of articles

on “work-life balance” is actually that exact phrase. The word “balance” seems

too positive a term for what is essentially a decision about what to sacrifice

in your life. The above examples from the piece in Nature have, although not

explicitly stated, sacrificed their social life in order to maintain work hours

whilst spending time with their children. That’s fine, but this sacrifice

should be explicitly acknowledged. Personally, I work slightly fewer hours than

I used to (trying to be more productive with those hours I am in the office)

and go out with friends a lot less. I have also sacrificed any time to myself

in the evening. Once my child is asleep I spend time with my wife, as we rarely

get time alone during the day. I consider this a relatively “balanced” life

considering how much upheaval a baby causes in one’s life, but I have had to

sacrifice quite a bit to reach that balance.

The point I am trying to make is

that a lot of talk about “balance” is directed towards cramming more stuff into

the same number of hours. Instead I think we should talk more openly about what

is and what isn’t important. What we can give up and what we need to maintain.

Only then should we discuss how we can use the finite number of hours allotted to

us to carry out the tasks that we have prioritised.

Friday, 9 January 2015

The academic parent #1 - guilt and multiple personalities

Preamble

I plan to blog occasionally about

being an academic and a parent. I’m not entirely sure what form this is going

to take. I’ll try to keep each blog short. Most blogs are unlikely to have a

moral or a valuable lesson to be learned. They are more likely to be a

reflection on something that has happened to me recently that I feel others

might be interested in. I believe this first post fits this description.

Note – I have been a parent for a few months. This is a ridiculously short period of time. All opinions are likely to change on a daily basis dependent on how much sleep I get the previous night and whether my daughter is teething. This should therefore very much be viewed as a snapshot.

My daughter was born seven months

ago. She’s now crawling around, making strange loud noises from her mouth (and

other body parts), and smiling copiously. It’s a genuine joy spending time with

her on a regular basis, and a genuine pain having to get up early every morning.

It’s the best thing I've done in my life.

I've been meaning to blog about

parenthood in some form for a while now (seven months in fact!), but strangely

enough have had very little time to do it. The first few weeks were a complete

blur. I took two weeks off, and then went back part time for a further 4 weeks.

Altogether this added up to about a month of paternity leave. Luckily I work

for an organisation that provides up to a month paternity leave at full pay. I

count my blessings (I don't know how people cope with two weeks - I would have taken more if I could).

Returning to work was a strange

sensation, and this is the topic of this first blog. When I returned to work it

seemed like I had been away for a long time, but of course nothing had changed.

Slotting back in to the regular daily routine was surprisingly easy – like sitting

down in a comfortable arm chair. The thing I found most difficult to deal with,

mostly due to how unexpectedly it appeared, was guilt. When at work, I was

thinking about being at home and felt guilty about leaving my wife alone with

the baby. When I was at home, I was thinking about being at work and felt

guilty about not getting enough work done. I then started to feel guilty about

thinking about work at home and thinking about home at work. It all got very

confusing and meant I wasn't working very hard nor being that great a parent.

I’ll return to guilt shortly.

First, I want to take a small detour to discuss multiple personalities. I've

always been a bit suspicious of people who act completely differently dependent

on context. Of course we all moderate our behaviour based on where we are and

who we are talking to, but I've always found it jarring when someone I know

well in a work situation acts like a different individual in a social context.

Having a baby has changed this. I now do whatever it is I have to do to make my

daughter smile. Baby smiles are like crack – highly addictive. If I have to

sing a stupid song, pull a stupid face, blow raspberries, so be it. I will sacrifice

my dignity at the altar of my child's happiness. I have never been a

particularly frivolous silly individual, so I have had to learn how to behave

in this way. I've essentially developed a new personality that would be wholly

inappropriate in a work setting. I now find it surprisingly easy to switch

between these modes of thought (if you can describe a set of behaviours that

mostly consist of doing stupid things as a mode of thought).

How does this relate to the guilt

I mentioned earlier? Put simply, having multiple personalities has cured my

guilt. My work persona now doesn't think too much about home. Equally, my home

persona cares not for the seriousness of work. The compartmentalisation has

made me more efficient at work and a better parent at home.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)